SENTRIES OF THE OZARK TRAILS

Written by Jim Ross

William “Coin” Harvey had a problem, and it was not of the garden variety. This one was a jawbreaker. The five-mile railroad spur he’d built from the St. Louis – San Francisco Line at Lowell, Arkansas, was not paying its way and service had been discontinued, leaving guests destined for his Monte Ne resort with no way to get there. They might as well have slipped an oversized garrote around the place and choked off the air supply.

Harvey never expected such a setback, given the popularity of Monte Ne, but he was not one to cower when the wind howls, either. As a lawyer, real estate developer, and one-time advisor to William Jennings Bryan, he subscribed to the theory that failures are best viewed as doors to opportunity. So with no time wasted he began strategizing to capitalize on the rising use of automobiles to bring tourists straight to his door.

William Hope Harvey made his money in Colorado silver mining. Born in West Virginia in 1851, he practiced law in the east for several years before seeking his fortune out west. He authored two books on finance in 1894 and was involved in Bryan’s presidential campaign in 1896. Along the way, his advocacy for the free coinage of silver earned him the nickname “Coin.” In 1899, with silver prices sliding, Harvey moved to northwest Arkansas where he bought 320 acres of land east of Rogers and over the next few years developed a resort near the White River that he named Monte Ne. According to Harvey, the name translated to “Mountain Waters.” With no road to his scenic wonderland, Harvey financed the railroad spur, only to see it abandoned in 1910.

With the Goods Roads movement on the upswing, Harvey jumped in with both feet. He first attempted to corral partners to build a toll road from Muskogee, Oklahoma to Monte Ne, but the effort failed. Undaunted, he feverishly pursued plans to create an entire network of roads within the states of Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Aptly named the Ozark Trails, his new organization squalled to life with its first meeting on July 10, 1913.

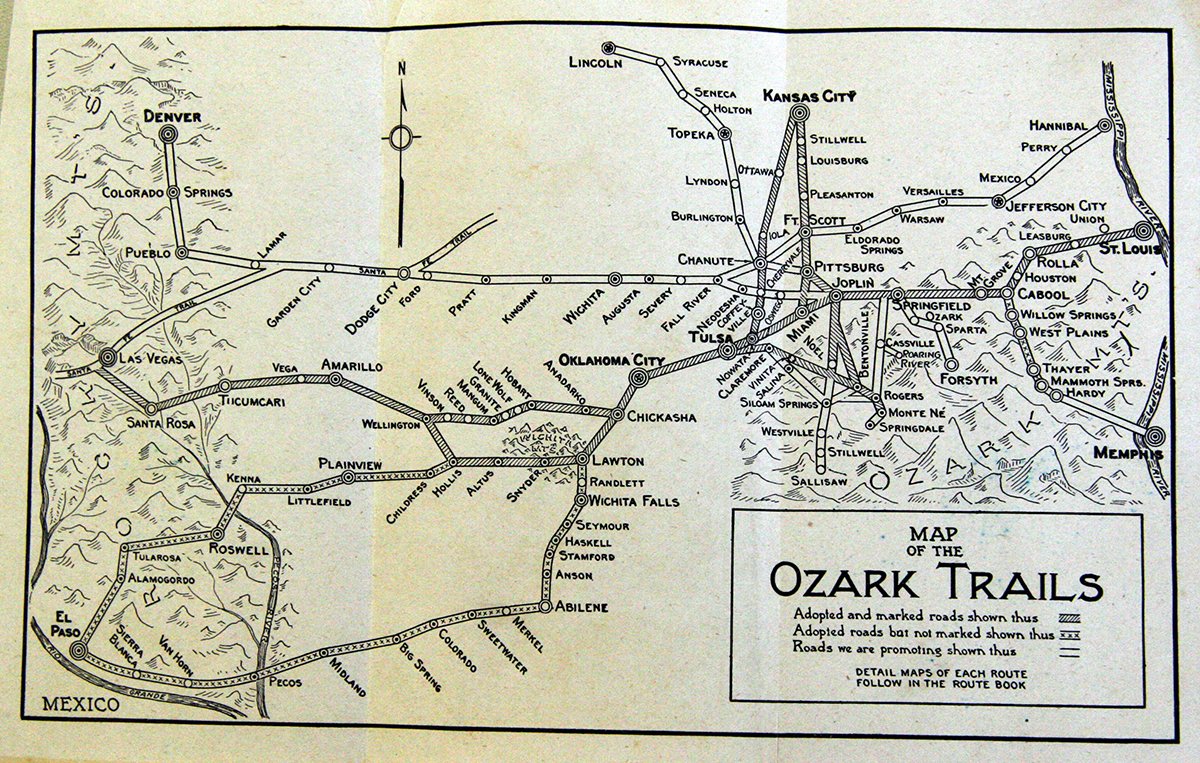

The purpose of the Ozark Trails Association was the establishment and promotion of improved roads. It was funded by $5.00 annual memberships and contributions from the good folks and civic leaders along the proposed routes. Over the next decade the Ozark Trails would spread beyond the original four states to include Colorado, Nebraska, Texas, and New Mexico as well, all anchored by a trunk line running about 1100 miles from St. Louis to near Las Vegas, New Mexico, where it linked with the Santa Fe Trail at Romeroville.

Yearly conventions were slated, where delegates elected officers, proposed routes, and lobbied for the site of the next meeting. These conventions rapidly evolved into an orchestrated tangle of motorcades, brass bands, impassioned speeches, politicking, and unchecked revelry. In some instances, having just one convention annually was not enough, so they added an “Adjourned Session,” held in the primary event’s runner-up city.

During the OTA’s lifespan, six meetings were held in Oklahoma, with the 1916 Oklahoma City gathering setting the high-water mark for both hoopla and attendance, with over 7,000 delegates on hand. It was a gala made more remarkable in that it was an “Adjourned Session” to the one held in Springfield, Missouri. Other Sooner cities to host the OTA were Tulsa, Miami, Shawnee, Sulphur, and Duncan. Not surprisingly, one of Harvey’s strongest supporters was the man destined to become the father or Route 66, Tulsan Cyrus Avery, himself an avid promoter of good roads. Avery brought the OTA convention to Tulsa in 1914 and became vice president. Once again, success had graced Coin Harvey with what was evolving into a groundswell.

Final selections for the main line route were decided in Amarillo, Texas, in 1917 after a whirlwind of nominating, campaigning, and rousing oratory. When the smoke cleared, the adopted route linked St. Louis with Las Vegas, New Mexico via Springfield, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Amarillo, and Tucumcari. Along this artery were multiple branches—some proposed, some adopted, some later marked, some not. In the coming years there would be many modifications and yet more branches. Over time, the Ozark Trails would morph into a spidery snarl of auto trails without discernable pattern or purpose. As its growth careened out of control, Harvey made no effort to bridle it. He was not about to stand in the way of his benefactor.

More important to Harvey was ensuring the OTA’s prominence on the motoring landscape. Promoters of dozens of other auto trails were competing for the attention of travelers, and it had reached the point where drivers were apt to be misdirected or become hopelessly confused when confronted with clusters of directional markers at intersecting routes. Harvey knew it would take more than a distinct logo and a legion of signs to nose ahead of the pack, and it wasn’t long before he had the solution.

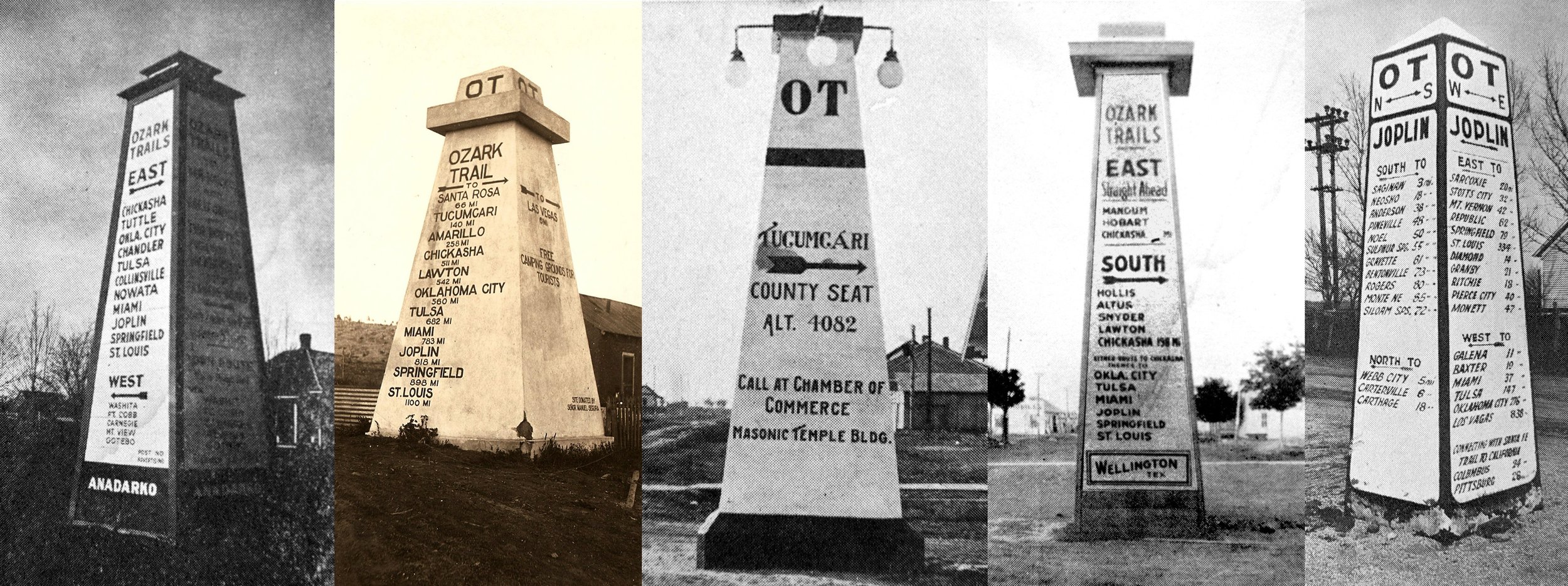

The OT would erect imposing obelisks, twenty feet tall, at strategic points along the route. They would be of a uniform design and contain the Ozark Trails logo as well as names and distances to upcoming towns. The first of the “pyramids” or “monuments,” as they were called, went up in 1918, with construction continuing until about 1922. Other than a few initially made of wood, they were cast in concrete, with lighting soon added to the design. Whether knowingly or unwittingly, implementing these monoliths created a hallmark that would ultimately enshrine the OT and guarantee its survival as a physical presence well into the 21st century.

Harvey stepped down as president of the OTA in 1920, though he retained almost total control. By now he was distressed over what he considered the ultimate demise of civilization, and his focus shifted to building a massive, 130-foot-tall pyramid at Monte Ne which would contain a time capsule holding artifacts of the era and writings (by Harvey) explaining the reasons for the collapse and how to successfully rebuild society. A plaque at the top would ensure its discovery in the event of natural disasters. The pyramid was never built, though the Monte Ne landscape was in fact headed for dramatic alteration when most of it became submerged following construction of Beaver Lake in the 1960s.

To Harvey’s credit, the OT provided improved and safer transportation for motorists and established pathways that would later be adopted by numerous US highways, including Route 66. On the flip side, the Ozark Trails ended up a contorted matrix of interlocking roads that were woefully documented and never fully marked, possibly due to poor oversight and because Harvey’s motives were inspired by personal gain. Only two route books were ever published—in 1918 and 1919, both before major changes came to the trails. The OTA began its decline even as obelisks were still going up, and it faded completely after 1924 following several years of organizational in-fighting and a cooling of confidence in the Trails’ future. Association records were lacking and even Harvey’s personal papers contained little of historic usefulness. He died in 1936.

Despite strenuous protests from many among the named trails organizations, the Ozark Trails found its identity on the scrap heap right alongside its contemporaries when the numbering system for US highways was implemented in 1926. Today, Harvey’s creation would likely be just another obscure entry among the hundreds of named trails that once existed, except for two things: the surviving obelisks, and the OTA’s relationship with US 66.

In Missouri, Kansas, and the eastern half of Oklahoma, Route 66 and the OT intertwined on a nearly continual basis. In western Oklahoma and in Texas, the path of the Mother Road ended up to the north of the Ozark Trails. In New Mexico, US 66 adopted the path of the Ozark Trails from Glenrio in the east to Santa Rosa, where the mainline OT route angled northwest to its rendezvous with the Santa Fe Trail at Romeoville.

Coin Harvey’s original idea was to build a dozen of the “pyramids,” with the one at the Santa Fe Trail junction to be twice as tall as the others. But as interest in the Ozark Trails (and the obelisks) grew, that number escalated. Precisely how many were ultimately built is not known, though the literature references more than forty. At a cost of roughly $250 each, they offered an affordable way for communities to boast of their association with the network. Ironically, most of the OT’s obelisks would vanish within a decade, either destroyed or buried where they stood, as many were in the center of intersections and came to be viewed as traffic hazards. Even so, seven of these time-worn landmarks survive—two in Oklahoma, four in Texas, and one in New Mexico. An eighth obelisk was exhumed from beneath the street—in pieces—in Stratford, Oklahoma in the early 1980s, reassembled, and now stands on a nearby horse ranch.

The first of these stalwart sentries is near Stroud, Oklahoma, once a crossroad for the Ozark Trails. The mainline route entered there from Depew to the east, turned south from Main St. at the intersection with 8th (today’s Highway 99) and stair-stepped along section line roads until it turned west to Davenport. An added branch of the OT moseyed into Stroud on 8th St. from the north via Sapulpa and Drumright, crossing the trunk line at Main, where an obelisk (now gone) was built in 1920. Southwest of Stroud, where the mainline route turned west to Davenport, the Drumright branch continued south toward Prague. Where the two parted company, another monument, still standing, was built to mark this split in the route.

The obelisk in Stroud was removed at an unknown point once US 66 markers went up. Records have not been found documenting its demise; likewise, nothing has been found documenting the construction of the obelisk southwest of town. This has led to speculation that the monument at 8th and Main was moved to the more rural site, however it would be pointless to move an OT marker standing on a US highway to a nearby location on the same US highway, given the mandate to remove them from US highways. Now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, this surviving edifice has not seen maintenance for years, unlike its counterparts in Texas and New Mexico, where the heritage and grandeur of the Ozark Trails is proudly recognized.

Tampico, Texas

Wellington, Texas

In addition to its southward turn at Drumright, the Sapulpa branch also continued west through Cushing and Langston to Guthrie and Oklahoma City. The Sooner State’s second obelisk sits off the beaten path in semi-obscurity along that route at E. Washington and Indian Meridian/S. Logan Ave. in Langston. At some point after 1926 it saw new duty as a commemorative marker for the eastern boundary of the great Oklahoma land run (the Indian Meridian) and thus was saved from demolition. Today it is recognized locally for this alone, but has not been restored or otherwise maintained.

Through geographical good luck, the Collingsworth County seat of Wellington, Texas, about twenty-five miles south of Shamrock and on the mainline route, became a hub for the Ozark Trails. The primary route via Altus, Oklahoma, as well as another branch, converged there. To the west, the mainline proceeded to Clarendon, with sub-routes to Tulia, Plainview, and Matador, Texas. As a result, the obelisk in the intersection at 8th Street and East Ave. in front of the courthouse contained directional information on three sides. This sentry of the Ozark Trails held its ground until around 1939, when it was carted off to a rural site and given the heave-ho. It remained in its shallow grave until found by a farmer in the mid-1980s and recovered. By then the city of Wellington had embraced its OT heritage, and in 1990 the obelisk, though shortened due to damage, was reinstalled at the northeast corner of the courthouse lawn.

The Wellington marker is the only survivor on the mainline through Texas. The remaining three were built on a branch that angled southwesterly from there toward Roswell, New Mexico. The first encountered is at Tampico, Texas, a wind-blown former railroad siding where there was a store, gas station, a small school, and nothing else. Tampico did not even rate a dot on the 1918 route book’s map. Its existence is likely owed to J.E. Swepston of neighboring Tulia, who succeeded Coin Harvey as OTA president in 1920 and was reportedly responsible for the erection of sixteen obelisks in Texas and New Mexico.

By the 1930s, the hamlet of Tampico had gone the way of the Ozark Trails. Today, this unlikely Hall County shrine still stands in the center of an unpaved road a short distance south of Hwy. 86 where Ranch Road 657 connects from the north. It is a setting strikingly similar to the one near Stroud, Oklahoma, and while it would appear fair game to vandals and ignored by everyone else, instead it is a gleaming preservation success story. All of this is thanks to archaeologist J. Brett Cruse of the Texas Historical Commission, who led an effort to have the obelisk designated a state archaeological landmark in 1999.

Nine miles west, Hwy. 86 passes through Turkey, home of “King of Western Swing” Bob Wills, and from there through Quitaque (Kitty-quay), another Ozark Trails community that is home to the Mid-Way Drive-In Theater as well as an OT obelisk, which is now buried beneath Main Street. About forty miles farther on, Tulia is the county seat of Swisher County and home to Texas survivor number three, which has stood reliably since 1920 at the intersection of Broadway and Maxwell next to the courthouse. In the spirit of its counterparts at Wellington and Tampico, the Tulia marker commemorates the shared heritage of the city, the Ozark Trails, and Swisher County.

The Lone Star State’s last obelisk is just thirty miles west in the Castro County seat of Dimmitt. Though it doesn’t display town names and distances, it stands prominently on the corner of the courthouse square at Bedford and Broadway, having been moved from its original position in the street. The site is enhanced with a plaque denoting the history of the courthouse as well as a federal aid project marker identifying 1938 road improvements there.

From Texas, the Ozark Trails into and through New Mexico was a convoluted affair. The trunk line fifty miles to the north followed future US 66 from Glenrio to Santa Rosa and on to Romeroville, where it terminated at the Santa Fe Trail. The branch from Dimmitt, Texas, continued west to Clovis, where it split, with one pathway aimed for Ft. Sumner and the other for Roswell. At Roswell, the OT split again, with one branch headed to El Paso by way of Alamogordo, while the other, adopted in 1920 as the Pecos Valley Route, headed due south toward Van Horn, Texas.

Thirty miles south of Roswell on that Pecos Valley Route, the lone surviving obelisk in New Mexico still directs traffic from the intersection of 5th and Main in the village of Lake Arthur. Built in 1921, it is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. And, like its Texas counterparts, it is beautifully maintained with town names and distances listed for both north and southbound motorists.

Five of these lofty holdovers have found new life as badges of community pride and as reminders that the growth of the auto age in America is rooted in the hard work of boosters and townsfolk determined to open the gates of travel. In Oklahoma, the obelisk near Stroud, while not endangered, is in need of guardianship, while its Langston companion suffers from a misunderstood identity. Even so, these seven surviving sentries of the Ozark Trails, whether their historic integrity is compromised or not, and excepting unwise acts of man or natural disaster, will continue to mark the fragmented paths of our motoring roots for decades to come. Whether his motives were dubious or not, Coin Harvey was a visionary whose efforts have left tangible marks on the motoring landscape, and that alone earns him a place in transportation history.

Dimmitt, Texas

Langston, Oklahoma

Tulia, Texas

OBELISK TRIVIA

All seven surviving obelisks are in small towns or rural settings.

An eighth obelisk was unearthed from the street in pieces in Stratford, Oklahoma in the early 1980s, was reassembled (somewhat shorter), and is now on private property about four miles from town.

Three of the seven obelisks are on routes adopted after the association’s route books of 1918 and 1919 were published—those at Tulia and Dimmitt, Texas, and the one at Lake Arthur, New Mexico.

Obelisks were first mentioned in the May 10, 1918 Miami (Oklahoma) Record-Herald and were described as having a four-foot square base, a two-foot square top and standing twenty feet tall. Early markers were made of wood, stucco, or concrete and varied in size and shape. Lighting was not added to the obelisk design until 1920. By then the standard design called for reinforced concrete to be set five feet into the ground.

At one time, Miami, Oklahoma had three obelisks.

Two obelisks, in Stroud, Oklahoma, and Lake Arthur, New Mexico, are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and one, at Tampico, Texas, has been designated a state archaeological landmark.

The obelisk at Bluejacket, Oklahoma was constructed of wood.

Obelisks at Wellington and Dimmitt, Texas, have been moved from their original locations in the street to the corner next to their respective courthouses. In addition, the Wellington marker was shortened after being recovered from its place of abandonment. All others remain in their original locations.

In addition to the obelisks listed below, there were likely additional markers built in the states of Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and elsewhere.

Surviving

Southwest of Stroud, Oklahoma (1920)

Langston, Oklahoma

Wellington, Texas (prior to 1920)

Tampico, Texas

Tulia, Texas (1920)

Dimmitt, Texas

Lake Arthur, New Mexico (1921)

Others Documented in Photos

Joplin, Missouri

Dawson, Oklahoma (Nine miles east of Tulsa at junction with branch to Arkansas)

Miami, Oklahoma (two, plus one documented in literature below)

Bluejacket, Oklahoma (four miles west of town at junction with Jefferson Highway)

Meeker, Oklahoma

Anadarko, Oklahoma

Tucumcari, New Mexico

Others Referenced in Literature

Lowell, Kansas

Buffalo, Missouri

Miami, Oklahoma

Drumright, Oklahoma

Perkins, Oklahoma

Stroud, Oklahoma (1920)

Chickasha, Oklahoma (1919)

Chandler, Oklahoma (2)

Cushing, Oklahoma

Hobart, Oklahoma

Quitaque, Texas

Artesia, New Mexico

Lakewood, New Mexico

Carlsbad, New Mexico

Four additional on the Pecos Branch of the Pecos Valley Route (from Malagna, New Mexico to Van Horn, Texas, via Pecos).

Fifteen additional built in the Texas Panhandle and in New Mexico’s Curry and Roosevelt counties.